内容提要:珠江三角洲是当今世界最大的巨型区域群之一。尽管学术界通常将珠江三角洲作为一个自然区域进行分析,但该地区直到最近才被区域化。本文对珠江三角洲的历史进行了批判性重绘。殖民前,中国人认为该地区是由岛屿和水道组成,殖民时期,列强将该地区视为从香港和澳门殖民岛屿飞地进入中国内地的通道, 改革开放后,中国政府针对该地区提出了一系列以规划为导向的区域理念。随着该地区在概念上从一个岛屿世界转变成三角洲,再到如今的粤港澳大湾区,人们对该地区的认知也发生了变化。本文从城市岛屿研究和批判性反思的角度出发,探讨殖民地、技术官僚、政府愿景与区域化之间的关系,重点关注该地区的自然和文化地理如何协同发展。本文采取的间隙岛屿视角有助于理解珠江三角洲的岛屿地理如何影响该地区的概念发展。

Abstract: The Pearl River Delta in South China is today associated with one of the world's largest megaregions. Even though scholarship often treats the Pearl River Delta as a natural region and unit for analysis, this area has only recently been regionalised. This paper undertakes a critical rewriting and remapping of the Pearl River Delta's history, starting in precolonial times in which the Chinese population saw the area as composed of islands and waterways, moving through the period when colonial powers saw the area as a pathway up from the colonial island enclaves of Hong Kong and Macao and into China's interior, and ending in the Reform and Opening Up era when the modern Chinese state has implemented a succession of planning-oriented conceptions of the region. As the area has moved conceptually from a world of islands to a delta and now to the Greater Bay Area, perceptions about what the area means have changed as well. From a position in urban island studies and critical reflexivity, this paper troubles taken-for-granted colonial, technocratic, and governmental visions and regionalisations, focusing on how physical and cultural geographies develop in tandem. The notion of the interstitial island is used to help understand how the Pearl River Delta's island geography has influenced the area's conceptual development.

1. Seeing the world

Our positioning in the world affects how we know the world, and our knowledge of the world affects how we act in the world (Qin, 2018). This positioning is geographical, cultural, temporal. We may move through many positions over time, as we develop, even when standing in place.

This is a study of changing conceptions of a particular geographical area. What are the consequences of perceiving a place in a certain way, of linking it up with other places into a region? How do vernacular, scholarly, administrative, and political processes interact with one another and with the physical geographies they seek to rationalise?

The area in question is today commonly called the Pearl River Delta 珠江三角洲. In one sense, the Pearl River Delta is an alluvial delta formed by the Pearl River as it enters the South China Sea. The Pearl River itself is a vast river system, carrying water and sediment down through much of South China, altering coastlines, eroding existing landforms, and creating new landforms. In this understanding, the Pearl River Delta proper consists of: the land and water in the lower reaches of the Pearl River system, the Pearl River Estuary 珠江口, and the clusters of rocky islands that mark the boundary between the estuary and the South China Sea. The Pearl River Delta is an object of physical geography: fluid and changeable, yet tangible. It is there, if we choose to see it.

However, the Pearl River Delta is not just (or even primarily) a matter of physical geography. It is also a matter of urban and political geography. Discussions of the Pearl River Delta today habitually focus on the urban agglomeration with which it coincides. The Pearl River Delta is said to be among the world's largest and most rapidly developing megacities or megaregions, a “geographic unit” joining diverse political and economic systems (de Jong, Chen, Zhao, & Lu, 2017). There is a tendency within Chinese social sciences and humanities scholarship to look back upon the history and development of the area encompassed by the Pearl River Delta as though it were a timeless unit of analysis, a space that it makes sense to study as a region regardless of whether one is researching ancient construction techniques or present-day ethnology.

Yet the idea of the Pearl River Delta has formed and shifted in meaning over the course of millennia. These lands and waters have been called different things by different people at different times, and the area's borders constrict or expand, emerge or submerge, depending on who is setting them. The Pearl River Delta was not always regarded as a delta. As recently as the 19th Century, it was seen primarily as a waterscape containing rivers and various more-or-less distinct islands and mountains. Its conceptualisation as a delta occurred, moreover, decades before the area came to serve as a metonym for the 20th and 21st-Century urban, economic, and demographic processes within it. Today, the delta is receding from view, as bay becomes the favoured conceptual container for the area, in the context of a changing China.

Taking an approach of critical reflexivity (Nadarajah, Burgos Martinez, Su, & Grydehøj, 2022) and informed by the notion of the interstitial island (Zhang & Grydehøj, 2021) in urban island studies, this paper explores the conceptual development of the Pearl River Delta as a region. We present the Pearl River Delta as an interstitial space in two senses: 1) The Pearl River Delta has served as an interface between China and the world, and 2) the Pearl River Delta has served as an interstice connecting different places within China, functioning as a cohesive medium at different scales. These explorations illustrate how conceptualisations of a region change as a result of the introduction of not just new actors and perspectives but also of new cultural, economic, political, and environmental realities.

By studying the Pearl River Delta in this manner, we contribute to the wider project of complicating and destabilising fixed and universal readings of space (Nadarajah et al., 2022). We also demonstrate how the field of island studies can offer novel perspectives on spatial organisation: The critical island studies perspective is not inherently more or less correct than alternative perspectives, but the very act of perceiving spaces in different ways emphasises the importance of situating scholarly knowledge and recognising the power relations within it. Finally, we hope to initiate new kinds of discussions about the potential pasts and futures of the Pearl River Delta itself, showing that the region's developmental direction has not been straightforward and is not bound by any laws of nature. The people of the Pearl River Delta can choose how they wish to conceive of the spaces in which they live.

The next section of this paper provides an overview of our theoretical perspectives from urban island studies and our approach of critical reflexivity, including how this applies to naming, mapping, and regionalising practices. The subsequent empirical portion of our study begins in prehistoric times, moves up through the 19th Century's clash between local and colonial spatial perceptions, attends to the scientific ‘discovery’ of the delta, and delves into the planning-driven regionmaking exercises of the late−20th and early 21st Centuries. The study's temporal and social breadth necessitates its reliance on a variety of methods. Underlying this paper's effort at a critically reflexive rewriting of the Pearl River Delta's history are analyses of a wide range of primary sources, including policy documents and maps, as well as reviews of the existing scholarly literature. We have been selective in our choice of documents to discuss, choosing to emphasise documents concerning Guangdong Province or the Pearl River Delta as a whole. A different selection of documents (for example, from the village level) would no doubt provide different insights. Although our broad perspective prevents us from drawing definitive conclusions about any individual regionalisation process, it permits us to make wider observations regarding change over time that could not be obtained through more focused research.

In order to discuss the various ways in which this region has been interpreted and deployed over time, we henceforth use the acronym PRD to refer to the object of physical geography and will limit use of Pearl River Delta to situations in which this object of physical geography is explicitly conceptualised as a delta. Where available, we use English-language place names, accompanied by the place names in Chinese characters, instead of using the pinyin system of romanising Chinese characters. There are three reasons for this choice: We wish to maintain the international comprehensibility of the geographical terms (e.g. delta, river, bay) under discussion, the English-language place names in question are generally straightforward translations from the Chinese rather than total exonyms or are the sources of the current Chinese placenames, and pinyin is arguably no less a colonial imposition than the English translations themselves.

2. Theoretical perspectives

Urban island studies is a subfield of island studies that emerged in the mid-2010s. As island studies made scholarly inroads in parts of Asia with which it had previously had little contact, island studies scholars began looking for islands in new geographical contexts. As a result, some international scholars ‘discovered’ China's near-shore, delta, riverine, lake, and lowland islands, and some Chinese scholars began inserting their studies of such islands into island studies. Although these places were readily identifiable as islands once exposed to the island studies gaze, they often differed from the kinds of islands and ideas about islandness that had hitherto dominated the international field. Despite frequently being conceived of in terms of remoteness and peripherality (Hong, 2017; Wang & Bennett, 2020), many of China's islands were densely urbanised and straightforwardly integrated into mainland urban systems. Traditional island studies struggled to cope with islands in, for example, China's Pearl River Delta, Yangtze River Delta, and the coastal waters of Fujian, not to mention river islands in the continental interior (Hong, 2020a).

Island studies’ tendency to associate islands with smallness and remoteness always risked oversimplification (Nimführ & Otto, 2021). As Hong (2020c, p. 238) notes, “There is usually a rupture between island experience and island representation. The status of being an island is not necessarily foregrounded in the experience of the island.” Yet islandness does not become meaningless just because experience and representation are disconnected. Many major cities are based on small islands, and many small islands are densely urbanised: Even when people do not perceive them as islands, “islands and cities coincide” (Grydehøj, 2015, p. 429). Urban island studies suggested that islands are and were preferred sites for particular kinds of urbanism due to their spatial advantages (involving territoriality, defence, and transport), while “land scarcity associated with island spatiality contributes to island settlements developing into cities” (Grydehøj, 2015, p. 429).

The island cities of the PRD itself (especially Hong Kong, Macao, and Guangzhou) exerted a substantial influence on the early theorisation of urban island studies. Furthermore, the subfield hosted research concerning cases from the PRD (Hong, 2017; Leung, Tanko, Burke, & Shui, 2017; Sheng, Tang, & Grydehøj, 2017; Su, 2017), though not concerning the PRD as a whole. The present article thus begins its existence by inhabiting the space of tension that surrounds urban island studies more generally: It applies an island studies perspective to places that are or were islands in a physical geographical sense (pieces of land surrounded by water) but that may no longer be regarded primarily as islands by their inhabitants and that are not regarded as islands at all by many international scholars.

Zhang and Grydehøj (2021) address this tension by considering the Zhoushan Archipelago as an interface zone that connects the cities of the Yangtze River Delta megaregion with one another as well as connects the megaregion with the wider world. This notion of the interstitial island helps resolve the problem of islands simultaneously being regarded as highly distinct, individual, and isolated places and as part of an abstracted periphery to the urban core. On the basis of the Zhoushan case, Zhang and Grydehøj (2021, p. 2170) argue that “certain core urban functions tend to occur on the periphery, at interstitial sites. […] Near-shore islands are particularly likely to act as interstices.” Certain kinds of island geographies are at their most island-like when creating links between places. Such links may be especially necessary in the case of spaces that are perceived as megacities or megaregions, products of a political-economic regionalising imagination that often rely on top-down conceptualisation and promotion (Dewar & Epstein, 2007; Harrison & Gu, 2021; Mukhopadhyay, 2018).

In the Yangtze River Delta megaregion, the urban centres are located on the mainland (Shanghai, Nanjing, Hangzhou, Suzhou, Ningbo, etc.), with the island interstices occupying the region's eastern fringe. This is not the case for the PRD, the core of which consists in large part of densely urbanised delta islands. Whereas Zhoushan is an interstitial island space at the edge of the Yangtze River Delta, the PRD as such can be perceived as an interstitial island space, albeit a space that formerly represented peripheral borderlands of the Chinese state.

We, as island studies researchers, are especially apt to ‘see islands’ when we look at the PRD, or indeed any other coastal area. The PRD's islands are—or in some cases, were—facts of physical geography, and they have influenced development within the PRD. We must nevertheless acknowledge that our analysis is framed in advance by the topic we study. Others who research the PRD have their own framings set by their own topical interests and disciplinary groundings, for example network approaches (e.g. Yang, Fan, Wang, & Yu, 2021, pp. 1–18) and ecosystem services and security approaches (e.g. Jiang et al., 2021; Liu, Wu, Chen, Fang, & Wang, 2021). While our island studies approach is no more legitimate than other possible approaches, it can potentially present new configurations and imaginations of the PRD. This is in line with movements within island studies over the past decade toward more nuanced understandings of island lives and the land-water interface (e.g. Cavallo, Vallerani, & Visentin, 2021; Fleury & Hayward, 2021; Grydehøj & Ou, 2017; Lei, 2021) and critical reflections upon fluid relationships between person, island, and water (e.g. Guerin, 2021; Joseph & Varino, 2021; Mahajan, 2021; Nadarajah, 2021; Schneider, 2020).

Such strands of research have benefited from the growing multidisciplinary attention being paid to delta, estuary, and ‘waterscape’ (Swyngedouw, 1999) geographies. In proposing an “amphibious anthropology, which aims to grasp how the confluence of land and water produces places and shapes human lives,” Gagné and Borg Rasmussen (2016, p. 139) suggest that “Landscapes are deeply entangled with human activities and linked to the movement of water. Human engagement with place requires knowledge of these movements, which are […] embedded in uneven epistemic hierarchies.” Bremner (2020, p. 24), exploring the ‘muddy’ and ‘sedimentary’ logics of South Asian delta zones, highlights the ways in which delta waterscapes unsettle “notions of territory as dry, stable or bounded.” Bhattacharyya (2021) similarly suggests that “silty littorals and oceanic frontiers must be seen as part of a hydrosocial and political history,” allowing documentation of “the colonial legal engagement and scientific puzzlement over this landscape.”

The present paper concerns how people and societies make sense of and organise space, including top-down efforts at turning a shifting range of places into a region. Deltas are naturally occurring phenomena, and regions are naturally occurring too—in the sense that people naturally form relations between places. However, the course and pace of regionalisation follows no fixed laws, and just as regions can be constructed, so too can they fragment and dissipate. Regionmaking is a complex and politically weighted process (Van Langenhove, 2016) involving a special kind of spatial imagination. However much powerful actors desire regionalisation, success in joining up places into regional space depends upon actors at all levels of society, from individual citizens to local governments to public and private companies. Rivers and deltas, like bodies of water more generally, can both connect places and divide them (sometimes successively and sometimes simultaneously) and can encourage actors to imagine new configurations of space and power, often to the benefit of particular groups (Bremner, 2020; Ho, 2014; Ivars, 2020). In the case of the PRD, 20th- and 21st-Century regionmaking efforts have been led by powerful social, political, and economic actors, especially by government bodies at the provincial and national level.

Berg and Vuolteenaho (2009, p. 6) emphasise how toponymical research and its associated methods of seeing and naming the world are always, inevitably, political and must be recognised as such. They are also always embedded in specific cultures in specific ways. Naming and discourse reflect culturally and environmentally embedded conditions and practices, and different needs give rise to different types of knowledge (Fei, 1992). The same is true for mapping practices and the cartographic process, which are always of their own time, place, technologies, and mindsets (Edney, 2019): When we consider maps, as we do in this paper, we must attend to that which maps either make manifest or paper over and conceal, which is something other than the physical world they purport to represent (Harley, 1988). Cartography can be a form of colonial claim-making, and the reconsideration of mapping practices can be a form of decolonial reclamation (Oslender, 2021; Rose-Redwood, Blu Barnd, Lucchesi, Dias, & Patrick, 2020). The present study thus challenges the naturalisation or taking for granted of the PRD as a region, as a named geographical entity, and as a mappable space. There are indeed senses in which the PRD exists in socially meaningful ways, but the PRD does not exist in a socially meaningful way for everyone, for all time, and that which the PRD signifies is subject to change.

As noted above, the island geographies of the PRD differ significantly from those that ‘mainstream’ Western island studies has tended to find interesting. Expressing concern about the uncritical scholarly application of Western island tropes to Chinese island cases, Hong (2022, p. 11) suggests that “non-western scholars writing into island studies [have] an opportunity to reclaim their own cultural experiences by disrupting hegemonic island discourses.” This dovetails with Nadarajah, Burgos Martinez, Su, & Grydehøj's (2022) call for greater ‘critical reflexivity’ in island studies, “opening up more explicitly and systematically to the concepts and cognates of alternative knowledges, lifeworlds, and languages,” while rendering untenable the “zero-point hubris” (Castro-Gómez, 2021) that takes Western conceptualisations as the baseline, judging and defining all phenomena accordingly. Appreciation of differences in perspective is critical to the pursuit of decolonial political geography and an island studies that is sensitive to relative positions of power (Grydehøj et al., 2021).

By undertaking a critical rewriting and remapping of the PRD's history, this paper troubles taken-for-granted colonial, technocratic, and governmental visions and regionalisations. Some of this writing is necessarily speculative, as for many centuries, local lives and voices were systematically delegitimised or erased by powerful social actors (Lin & Su, 2022). By the same token, precisely because the PRD as a region is an anthropogenic construct, the development of which has been led from outside and from above, during a period of immense cultural, economic, political, and environmental change, it is impossible to consider the history of the PRD from any one specific local perspective, much less to regard that perspective itself as timeless (Crossley, Siu, & Sutton, 2005). The perspective of the historic Dan boat people, for example, has been less frequently represented in scholarly writing on the PRD as a region but is no more or less objectively legitimate than, say, the perspectives of provincial planners, colonial authorities, or Han dockworkers. Our study thus maintains focus on how the physical and conceptual characteristics of the PRD have developed in tandem, how the PRD as an object of physical geography has related to the PRD as an object of cultural geography and an object for planning. The very act of describing and analysing conceptual instability and contingency is radical.

3. Remapping the PRD

3.1 The PRD as a space of islands and waterways

A typical history of the PRD's early development might go as follows: The PRD has been subject to vast movements of people and cultural mixings over the millennia. The region's favourable geography—at the intersection of riverine and oceanic transport networks—occasioned early urbanisation. Guangzhou had formed the rudiments of a port city already in the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BCE), eventually serving as the capital of the Nanyue Kingdom (204-111 BCE). In the wider Qin and Han Dynasties (221 BCE-220 CE), the city was an important base for foreign trade (Chen, 1996, pp. 232–234), even as it remained part of China's southern borderlands, peripheral to centres of state power. By the Tang and Song Dynasties (618–1279 CE), Guangzhou had become one of China's leading port cities (Zhang & Ye, 1992, pp. 213–216).

In the second half of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 CE), foreign trade intensified, and 1580 saw the establishment of biannual trade fairs in Guangzhou (Tang & Yan, 2005, p. 106). The implementation of a foreign trade ban in the early Qing Dynasty (1644–1684 CE) (Liu, 2012, p. 23) was followed by the establishment of a customs system in Guangzhou in 1684, and Guangzhou's Thirteen Factories 十三行 came to function as an official trade organisation of the Chinese state and later as a kind of free trade zone for commercial dealings with the West (Liang, 2009).

Portugal had established a colony on the then-island (today, peninsula) of Macao in 1553. The end of the First Opium War in 1842 gave Portugal the opportunity to expand the Macao colony and allowed the British to establish a colony on Hong Kong Island. The entrepôt services in these colonies helped drive the economy of the wider PRD (Deng, 1999), though foreign trade activities in Guangzhou proper increasingly relocated to port cities elsewhere in China in the wake of the Second Opium War (1856–1860) (Lin & Su, 2022). The PRD has thus served as an interstice between China and the outside world for over two millennia.

The above account ignores, however, the ways in which the PRD's waterscape and the ideas concerning it changed over time. After all, the PRD has not always been the Pearl River Delta. Upriver anthropogenic activities caused silting in the bay and produced a proliferation of shifting islands and coastlines anchored by mountains and rocky outcroppings (Wu & Zeng, 1947). This process gradually accelerated from around two millennia ago, with upriver cultivation causing the formation of mud flats, which were subsequently reclaimed as farmland (Xu, 2006, pp. 18–19). Both natural and artificial landforms underwent continual morphological change, with coastlines expanding and disappearing, islands emerging and submerging.

How did the people of the PRD think of the waterscape in which they lived? We have only limited knowledge of worldviews from the distant past as well as of vernacular (as opposed to literate and elite) worldviews of the more recent past. However we can glean some insight from placenames in the area. Although a typical cartographic view of the area would today suggest, for example, that Guangzhou is a thoroughly mainlanded city, linked to the Pearl River Estuary by the Shizi Channel 狮子洋, the city abounds with placenames that either directly label sites as islands (洲, 岛) or refer to terms associated with islands in Chinese culture (沙, 山, 石, 岗, 档, 礁, 排). In addition to Guangzhou's river islands, there are numerous offshore islands in the estuary that are unambiguously regarded and labelled as islands, such as Hengqin Island 横琴岛, Dong'ao Island 东澳岛, Qi'ao Island 淇澳岛, and Wailingding Island 外伶仃岛.

Even as the PRD grew increasingly urbanised, and land reclamation altered the waterscape to better serve perceived human needs, awareness of the waterscape's transition from small islets to larger delta islands remained. The 1853 Local Records of Shunde County state that “In the past, to the south of the Nanling Mountains, there was only sea, which gradually formed into islands and then gradually grew into townships” (qtd. in Ye, 2020, p. 3; translation our own). These same 1853 records include a map showing the distribution of military garrisons in Shunde, in present-day Foshan (Fig. 1): The map presents the area as composed of numerous water spaces and islands, the latter of which are labelled with the names of villages, garrisons, government offices, and topographical features.

Over time, the PRD's waterscape changed. For example, White Goose Pond 白鹅潭, which is today simply a split in the Pearl River in the west of Guangzhou, was formerly a larger expanse of water containing numerous sandy islands, such as Huangsha 黄沙, Shamian 沙面, Aozhou 鳌洲, and Baihezhou 白鹤洲 (Zeng, 1991, p. 7). All except for Shamian are now incorporated into the present-day mainland, a process that also occurred in the Ming Dynasty with Guangzhou islets such as Zhuhengsha 筑横沙 and Wuzhou 五洲 (renamed as Taipingsha 太平沙 in the early Qing Dynasty). The large reef Haiyin Rock 海印石 was only joined to the mainland in the early 20th Century (Zeng, 1991, p. 8). Haizhu District 海珠区, in the centre of the city, appears at first glance to be one large island but is in fact composed of numerous historical small islands and islets (e.g. 海珠岛, 河南岛, 官洲岛, 和丫髻沙岛).

Individual PRD islands had long served as interstices between China and the wider world. Most obviously, Hong Kong and Macao functioned as colonial island entrepôts. However, 19th-Century Guangzhou itself was dotted with more-or-less formalised colonial island enclaves: Shamian was a British-dominated enclave subject to Western utopian imaginings (Lin & Su, 2022), Changzhou Island 长洲岛 and Xiaoguwei Island 小谷围岛 were known in English as Dane's Island and French Island respectively due to their use by Danish and French vessels and industries, and Pazhou Island 琶洲岛 (formerly known as Whampoa Island 黄埔岛) hosted a Chinese customs office to mediate foreign trade (Fig. 2). Pazhou Island would eventually become the home of today's Guangzhou International Convention and Exhibition Centre, which hosts the important Canton Fair.

Care is needed, however, when discussing colonial island enclaves in the PRD. There is no doubt that foreigners made the most of the territorial, defence, and transport advantages associated with small island spatiality to develop them as interstitial sites that provided an interface between China and the rest of the world. Nevertheless, through to the end of the 19th Century, islands accounted for a large proportion of land in the area. If we today, for example, regard the late-19th-Century colonial enclave of Shamian as exceptionally islanded, it is because the island character of the remainder of Guangzhou has become less visible over time and because the Westerners who lived on and visited Shamian were keen to conceptually distinguish it as something utterly different from the Chinese Guangzhou surrounding it (Lin & Su, 2022). For Chinese people living in the PRD, the colonial enclaves were no more island-like than many other places. Because of Guangzhou's dense network of waterways, boats were essential for transportation throughout the city, and people's daily lives were strongly influenced by island geographies (Ye, 1999, p. 17; Zeng, 1991, pp. 8–9). Many people, particularly of the Dan ethnicity, lived aboard boats docked in the rivers. Guangzhou is still regarded as a water city 水城, a Chinese concept that links together cities in disparate inland and coastal wetland environments, pointing again to the cultural contingency of spatial understandings. The PRD existed as an object of physical geography, and it undeniably affected people's lives, but people viewed themselves primarily in relation to their own environments, contexts, and experiences.

There is little to suggest a specifically archipelagic understanding of the PRD: The Chinese population saw their world in terms of islands and water but did not conceptually connect islands into distinct groups. Hong (2022, 2020a) notes a general Chinese disinclination toward thinking with archipelagos, and we might bear in mind that peoples whose lived experience consists solely or primarily of islands and water frequently conceive of islands and archipelagos differently from mainland peoples (Grydehøj, Nadarajah, & Markussen, 2020). We must, indeed, take care not to be misled by our own island studies gaze, which can cause us to foreground island geographies where the islanders themselves perceive various constellations of land and water. It is in any case evident that the PRD's islands were not regionalised prior to the 20th Century.

3.2. How the PRD became the Pearl River Delta

Despite the prevalence of colonial island enclaves, the colonial imagination did not foreground the PRD's islands. The deepening of colonial interest and power in the 19th Century caused Europeans to conceive of the PRD as a set of water routes leading from Macao and Hong Kong, up to Canton/Guangzhou, and then into the Chinese interior. Fig. 3, for example, is one of many British colonial-era maps of the PRD that treats the contents of the islands and terrestrial spaces in general as being of no account. Fig. 4, a German map from 1834, offers tremendous detail regarding sailing routes through the estuary and rivers, but terrestrial features outside of Hong Kong and Macao are reduced to mere navigational aids, for instance in the series of silhouettes of islands and mountains on the horizon, in the lower-right corner of the map. These colonial maps contrast starkly with the mid-19th Century Chinese administrative map (Fig. 1) considered above: Chinese maps of the period give less attention to the precise tracing of coastlines and shipping routes and more to the contents of the islands and other terrestrial spaces.

Up until the end of the 19th Century, the PRD seems to have been perceived by its Chinese inhabitants as a space of islands and waterways and by Western colonisers as a series of paths that granted access to inland resources. Inasmuch as the PRD was discussed as a region or a cohesive whole, it was as the Yue River Plain 粤江平原, hinting at the importance of the flood plains and wetlands in which people actually lived. In contrast, the idea of a Pearl River Delta 珠江三角洲, which emerged in the early 20th Century, suggests a cartographic or outside-in understanding of the area, one that perceives the river system, delta islands, and wider waterscape from a distance, abstracted from people's daily lives.

Such differentiation between island and delta visions of the PRD may appear irrelevant. The PRD is, after all, technically speaking a delta 三角洲. It was first scientifically labelled as such in 1915 by the Swedish engineer G.W. Olivecrona, who came to Guangdong Province to undertake flood control work and determined that the plain stretching from Guangzhou to Macao was once a bay, which gradually coalesced into the Canton Delta due to sedimentation from surrounding rivers (Zhao, 2018, p. 2). In 1929, the American geographer G.D. Hubbard (1929), who visited Lingnan University, deployed the term Pearl River Delta when discussing sea level change, neotectonic movement, and geomorphology in the estuary.

In 1947, Wu Shangshi and Zeng Zhaoxuan published an influential paper describing the region as a composite delta that had a distinct model of land formation from those of many other large rivers: The platforms and hills in the delta (e.g. Baiyun Mountain 白云山 in Guangzhou, Wugui Mountain 五桂山 in Zhongshan, and Xijiao Mountain 西樵山 in Foshan) were formerly bedrock islands in a shallow sea. Sediment carried by the Pearl River system gradually silted and expanded around these islands, connecting them to form land, and creating a delta with a unique river network and topography (Wu & Zeng, 1947). Following the publication of Wu and Zeng's paper, Pearl River Delta was established as the official name for this area.

The fact that it was engineers and geographers who turned the PRD into the Pearl River Delta is significant. Its conversion from a lived-in waterscape to a scientifically grounded delta represents the prioritisation of technological rather than human sensory mechanisms and definitions. Bremner (2020) and Bhattacharyya (2021) have been attentive to how delta waterscape fluidity and lack of fixity have lent themselves to political, governmental, and colonial experimentation. While fluid boundaries can challenge efforts at fixing territory, they also provide flexibility for those seeking to deploy territory in creative ways.

3.3 From the Pearl River Delta to the Greater Bay Area

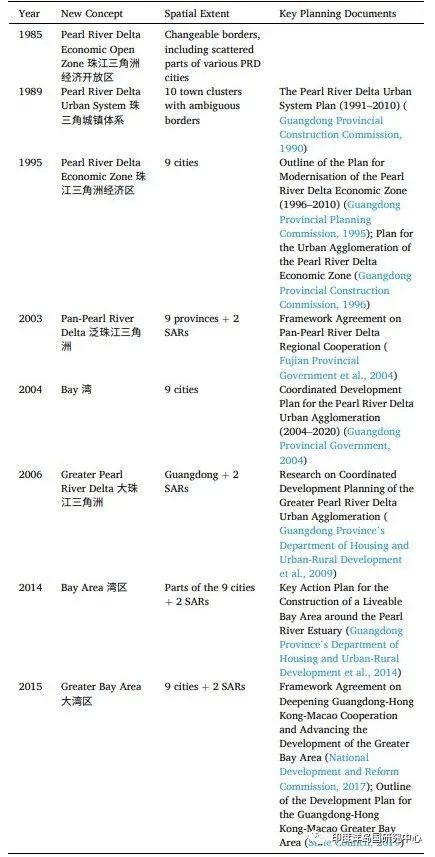

After 1949, in the era of the People's Republic of China, the PRD acquired new significance, and the concept of the delta region could be deployed for thinking about a reversal of the flows of power: Power could be projected from the Chinese mainland, down through the delta, and out into the world. Since the late 1970s, the cities and territories of the PRD have gradually transformed into an integrated economic region. This has been facilitated by the deployment of conceptual tools that render the PRD an appropriate and conceivable object for planning. The following review of the PRD's conceptual development draws upon a range of formal planning documents, mostly originating at the provincial level, which are cited in Table 2 below.

Table 2. Development of regionalising concepts centred on the PRD.

At the start of the Reform and Opening Up era in the late 1970s, the PRD was not managed as a region. With the exception of the then-colonies of Hong Kong and Macao, the entirety of the PRD (as we define it here) was encompassed by China's Guangdong Province, which is much larger than the PRD itself. Beginning in the mid-1980s and over the course of subsequent three and half decades, the PRD formed the centre of a series of distinct regionalising concepts with fluctuating and vastly different spatial extents.

The conceptualisation of the PRD as an economic region was preceded by efforts to encourage economic development in particular PRD cities. Shenzhen and Zhuhai were approved as China's first special economic zones in 1980, aimed at facilitating cross-border relations with Hong Kong and Macao respectively. In 1984, Guangzhou became one of China's 14 Open Coastal Cities, and the Pearl River Delta Economic Open Zone was established a year later, offering preferential treatment to export-oriented companies. Guangdong's provincial government responded to rapid development by strengthening regional coordination, and in 1989, the province began work on a spatial development plan for the Pearl River Delta Urban System, a region that, like the Pearl River Delta Economic Open Zone, had ambiguous or contingent borders. The early steps in the PRD's regionalisation were thus focused on constructing an interstitial zone to connect the Chinese mainland with the island enclaves at its border.

In the mid-1990s, the provincial government sought to coordinate development in a newly formalised Pearl River Delta Economic Zone. This involved integrated urban and rural spatial planning and the establishment of a hub-and-spoke system: Guangzhou was designated as the centre point, with development axes running out toward Zhuhai and Shenzhen, though already by 2000, Shenzhen had developed into another regional centre (Chen, Xu, & Xue, 2004, p. 29). Crucially for the imagination of the PRD as a region, the mid-1990s spatial planning introduced the idea that the Pearl River Delta consisted of the nine Guangdong cities surrounding the Pearl River Estuary: Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Foshan, Jiangmen, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Huizhou, and Zhaoqing (hereafter, the nine cities).

The colonies of Hong Kong and Macao returned to China in 1997 and 1999 respectively and became special administrative regions (SARs) just across the border from Guangdong. The launching of the Pan-Pearl River Delta concept (also known as the 9 + 2 Economic Region) in 2003 greatly expanded the region's spatial scope, focusing on cooperation among the nine provinces (Guangdong, Fujian, Jiangxi, Guangxi, Hainan, Hunan, Sichuan, Yunan, and Guizhou) and two SARs that neighbour the PRD. A year later, national-provincial collaboration led to the creation of a coordinated development plan for the Pearl River Delta Urban Agglomeration. For our purposes, this plan is important for formally introducing the concept of the PRD's nine cities as a bay 湾. With the Pearl River Delta concept expanding beyond the PRD proper to include the whole of South China, it became necessary to create a new regional concept for the delta as such.

In the late 1990s, scholars and researchers had begun developing the concept of the Greater Pearl River Delta, perceived as consisting of either the nine cities and the two SARS or the whole of Guangdong and the two SARS (Qin, 2006, p. 98). It was the latter interpretation that prevailed when, in 2006, Guangdong, Hong Kong, and Macao embarked upon their first joint regional planning exercise, a project that officially introduced the Greater Pearl River Delta concept as well as marked the first official inclusion of not only the nine cities but also the SARs within the bay area. That is, the identities of the jurisdictions cooperating in the planning exercise affected the contents of the region.

In the late 2000s and early 2010s, Guangdong province, the SAR governments, and the national government engaged in action-oriented collaboration to integrate the economies, infrastructures, markets, and ecosystems of what came to be conceptualised as the Bay Area, consisting of the SARs and parts of the nine cities. In 2015, a major national-level policy document focused on the Belt & Road Initiative made reference to the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, encompassing the entirety of the nine cities and the SARs (State Council, 2015). The Greater Bay Area concept has been further deployed in important national, provincial, and SAR government planning documents over the subsequent years. Marketing for the new regional concept frequently features comparisons with the San Francisco Bay Area in terms of their similar high-tech industry positioning and economic system and development mode (e.g. Hu, 2021). This indicates recognition of the bay concept's usefulness for regionalising the PRD proper while allowing the Pearl River Delta to continue serving as an organising concept for the economic integration of South China as a whole.

4. Analysis

The above account shows a development over time in ideas concerning the PRD. Prior to the 20th Century, most Chinese inhabitants of the PRD regarded it as a waterscape consisting of a mix of islands, mountains, floodplains, and waterways. Numerous individual islands in the PRD served interstitial functions in the sense that they were used by foreign states (e.g. Hong Kong, Macao, Shamian, Changzhou Island, Xiaoguwei Island) or by the Chinese authorities (Pazhou Island) to mediate interaction between China and colonial powers. The PRD as such was not an interstitial site because the PRD as such had not yet been regionalised. Colonial maps illustrate a perception of the PRD as a series of waterways and passages leading from the island enclaves of Hong Kong and Macao and up into China's resource-rich interior. Beyond the formal colonies at the mouth of the estuary, the terrestrial and lived-in spaces of the PRD were largely invisible to the colonial gaze. Westerners may have seen Chinese cities and communities as chaotic, incomprehensible, and impenetrable (Lin & Su, 2022) or merely as obstacles to be sailed past. They in any event emerge as blank spaces on the Western map, as irrelevant to the projection of colonial power.

In the 20th Century, as China began to once again project its own power back out into the world, scientific and technical recognition of the PRD as a delta facilitated the development of the PRD as a natural object for planning. Even so, at the start of the Reform and Opening Up era in the late 1970s, there seems to have been little understanding of the PRD as a region. Rapid economic development in the 1980s and early 1990s prompted shifts in the approach of Guangdong's provincial government. These shifts had less to do with the government's recognition of existing relations and connections within the PRD than they did with the government's recognition that more centralised planning had become a necessity in the most densely populated and rapidly developing parts of the province. The delta became a conceptual tool for binding together disparate cities and territories into a single planning regime.

The Pearl River Delta's success as a conceptual container encouraged a widening of the concept's spatial scope. The Pan-Pearl River Delta concept exploded the notion of the delta so that it encompassed the whole of South China, offering a rationale for linking up supply chains and creating industrial synergies on the strength of the PRD's export-oriented economic prowess. The power of the Pearl River Delta as a regionalising concept was thus drawn upon to achieve political and economic ends that were remote from those in which the concept originated, in much the same manner as China's Belt and Road Initiative today redeploys and massively expands the premodern Silk Road imaginary (Xie, Zhu, & Grydehøj, 2020; Winter, 2019).

Yet the spatial expansion of a concept comes with risks. If the idea of the Pearl River Delta had been important for creating cohesion between the cities surrounding the Pearl River Estuary and rendering them an object for planning, how could this sense of regionalism be maintained at a time when the government was stretching the delta concept to spatial extremes? It is here that the bay concept emerged as significant, beginning in 2004 and gathering strength and definition thereafter. The bay could replace the delta as the regionalising concept for the PRD's nine cities and two SARs, giving shape to the desired megaregion. The normalisation of the Greater Bay Area was necessitated precisely by the conceptual explosion of the Pearl River Delta over the previous decades.

As we have seen, the Greater Bay Area is very much a government-sponsored, top-down regionalising concept. Moreover, the central government has in many respects led the implementation of the concept. The government's own communications regarding the Greater Bay Area are technical, prosaic, and business oriented. For example, the Greater Bay Area's dedicated website focuses largely on investment promotion, emphasising the unique industrial strengths of each of the region's constituent jurisdictions (Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, 2021). The PRD is at once a geographical interstice between China and the world and a conceptual interstice facilitating and justifying interaction between PRD cities, including cities that have not been identified as key nodes of the region (e.g. Dongguan, Foshan, Huizhou, Jiangmen, Zhaoqing, Zhongshan).

There have been numerous studies concerning the relative attractiveness or lack of attractiveness of various Greater Bay Area cities for residents of the PRD or wider China, especially for residents of Hong Kong (e.g. Chan & Shek, 2021; Kirillova, Park, Zhu, Dioko, & Zeng, 2020). Such research suggests that perceptions of the region's coherence vary depending on the home places of the people being questioned and on the precise aspects being studied (opportunities for tourism, education, economic opportunity, innovation, etc.). Precisely because the Greater Bay Area has been a government-led project, targeted largely at other government bodies and at business actors, little attention has been granted to vernacular understandings, to the extent to which and in what ways residents of the PRD feel that the PRD is a region. With some exceptions, the state has not prioritised convincing the public that the region should mean anything to them. Inasmuch as strong feelings about the regionalisation of the PRD can be perceived among the public, these may be most evident in Hong Kong, where some scholars identify resistance to regionalisation and perceived “homogenization” (Yuen & Cheng, 2020) as a persistent challenge (Ng, 2020).

Does it matter that the government now presents the peoples and places of the PRD as being connected by a bay rather than a delta? If the Greater Bay Area concept has gained little purchase in the vernacular sphere, then this shift in official regionalisation may be irrelevant, though it is difficult to say with any certainty in the absence of further research.

What, however, has happened to the islands in all this? As we have seen, whereas pre-20th Century Chinese visions of the PRD seemed to focus on particular islands, mountains, and waterways, the official regionalisations of the PRD have not really cared about the details of physical geography. Even when the bay is foregrounded, it is a blank space in the centre of a triangular region. What do islands matter?

Because islands are commonly viewed not only as distinctive places but also as remote and peripheral in the Western mindset, it is common to think of islandness as the opposite of mobility and connectivity. This is certainly not the case for the delta islands of the PRD, either today or in the past. As Zhang and Grydehøj (2021) note, using an interstitial island perspective, certain senses of island place and of islandness within space are heightened or activated by particular connective processes and technologies. In waterscapes characterised by multiple islands, differences in degrees or types of connection to and separation from other places become critically important for how people conceive of islandness. Water transport, air transport, and fixed links (bridges, tunnels, causeways) that connect islands to other places can draw islands into urban and archipelagic systems, granting new island-specific meanings to formerly conceptually neglected places while also altering the perceived islandness of places that possess different kinds of connections (Grydehøj & Casagrande, 2020). Within complex urban systems, islands as such may have special roles to play—even when, as in the PRD, it is possible to conceive of much of the terrestrial environment as consisting of islands.

The development of the PRD from a place of islands and waterways into a delta and then into a bay has accentuated certain urban island functions and senses of islandness. In today's PRD, a large number of islands are commonly regarded as existing in contrast to or serving special functions relative to the conceptually de-islanded PRD ‘mainland’: Hengqin Island is simultaneously an economic enclave for Macao SAR and a leisure enclave for Guangdong; Yeli Island 野狸岛 and Hebao Island 荷包岛 are different kinds of leisure enclaves for Zhuhai and other cities; Shamian is a cultural heritage enclave for Guangzhou; Xiaoguwei Island 小谷围岛 is now an educational enclave, largely occupied by the Guangzhou Higher Education Mega Center; Cheung Chau 长洲 is a relaxing leisure enclave for busy Hong Kong SAR, and Coloane 路环 serves the same purpose for Macao SAR. This is less a continuation of the tradition for colonial island enclaves and more an indication that such potentials for enclavisation have always characterised PRD islands. Now that the PRD is conceived of as a region with a bay at the centre, the islandness of its enclaves has become more visible than it was in the past, when the PRD was not a region and when its residents saw islands as the rule rather than the exception.

In his urban island studies of Zhuhai, Gang Hong has focused precisely on such enclavising tendencies in the PRD. “Instead of just coming into being, Zhuhai was virtually called into existence by the central government” in the Reform and Opening Up period (Hong, 2017, p. 15), as the state used cross-border trade with Hong Kong and Macao to spearhead greater economic openness. The PRD cities' interstitial island spatiality (their role in mediating exchange between China and the world) was historically significant as a means of ‘mainlanding’ China's interior (Hong, 2017, p. 16). That the PRD's various core cities themselves now turn to exurban, peripheral, or even just spatially distinct islands as economic, leisure, and cultural enclaves does not point to a disappearance of islandness from these core cities so much as it points to further developments in the sense of what islands are ‘good for’. In Hong’s (2020b, p. 51) words:

Mainland–island relations may be interpreted as a relationship between self and other, in which self's identity is formed through constant engagement with other (Edgar & Sedgwick, 2002, pp. 168–170). Mainland society's enclavising tendencies with regard to islands betray a desire to escape its own reality by constructing a utopia that is both away and accessible.

If recognition of islandness requires the notion of a mainland, then the opposite might be true as well: It may be the peripheral, marginal, or enclavised islands that permit the PRD's urban core to be mainlanded. The foregrounding of their islandness allows the urban core to construct itself as something more solid than just China's pragmatically useful interstitial zone, even as this conceptual mainlanding—this replacing of the lived-in waterscape with a hard-bordered terrestrial region encircling a bay—prompts a reactive urge to embrace the island. Island enclaves are not just created for some place, they are created within some place (Hong, 2020b).

5. Conclusion

The PRD is changing. It has always been changing. Place itself and cultural, scholarly, and political imaginations of place have an iterative, mutually constitutive effect upon one another.

In this paper, we have studied how the PRD is an object of physical geography that powerful social actors have come to conceive of as a region. Various concepts have been used to link together different cities and places in the PRD, with the delta and bay serving as symbolic interstitial spaces that tie the region together. The impetus for conceiving of the PRD as a region in the first place came from the role of existing enclaved zones in the area, islands that served as interstices between China and the wider world. The PRD's waterscape is a result of millennia of human activity. Similarly, the conceptualisation of the PRD as a region is both cumulative and contingent. It is a kind of spatial politics dependent upon the interaction of diverse social actors, and just because the government encourages regionalisation, there is no guarantee that the regional concept will gain acceptance among the public.

The present paper is simply a start. We have approached this work in a spirit of critical reflexivity, which is evident in our efforts to accord equal status to different kinds of narratives of place and space and thus to recognise states of changeability, unsettledness, and continual development. Our work indicates how a critical island studies perspective can provide new ways of seeing, reading, and writing even a well-studied area or region, and more specifically it shows the PRD's potential to be imagined in new ways by the people who live there.

More research is necessary to understand how the people of the PRD feel about the area now and have felt about it in the past, to deepen our appreciation of where local and non-local, state and public, and place-specific perceptions align and diverge. In particular, more research is necessary that seeks to understand what the region means and where the region begins and ends for both individual residents of the PRD and for PRD communities whose voices are frequently absent from scholarly research concerning the region as such.

(参考文献与注释略)

【本文系国家社科基金项目(编号17CZW060)阶段性研究成果】

英文标题

Regionmaking and conceptual development in South China: Perceiving islands, the Pearl River Delta, and the Greater Bay Area

作者简介

苏 娉:华南理工大学印度洋岛国研究中心研究员

葛陆海(Adam Grydehøj):华南理工大学印度洋岛国研究中心讲座教授

文章来源

Political Geography

Volume 98, October 2022, 102668

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102668